It’s been an interesting few weeks for anyone studying how cosmic radiation and solar activity affect safety-critical electronics. We saw Airbus order the grounding of around 6,000 A320-family aircraft worldwide (with around 900 aircraft requiring fortifying hardware upgrades) after investigators concluded that intense solar radiation could corrupt critical control data mid-flight.

And NASA’s Perseverance rover captured the sound of ‘mini-lightning’ crackling on Mars for the first time. These static-like discharges, generated by colliding dust grains, were evidenced via electromagnetic interference picked up by the rover’s microphone.

This kind of cosmic radiation and electromagnetic interference (EMI) can disrupt sensitive electronics and instrumentation by flipping bits in a semiconductor’s registers, flip‑flops and memories. Such single‑event upsets can corrupt the processor’s internal state in ways that are hard to predict and potentially catastrophic to its operation.

Breker: No Stranger to Mission-Critical RISC-V Verification

That’s where Breker comes in. There are few industrial frontiers where our functional verification portfolio hasn’t been deployed to ensure complex semiconductors stay robust against the toughest operating conditions. These are processors destined for mission-critical systems for which failure is simply not an option: autonomous machines, industrial robots, advanced driver-assistance and autonomous vehicles, avionics, high-reliability infrastructure and other applications in which a single undetected bug or bit-flip can have serious consequences.

We’re no stranger to RISC-V, either. Our SystemVIP test suites have already supported more than twenty commercial RISC-V deployments on Earth through comprehensive verification.

Space, however, forces you to think very differently.

So when Frontgrade Gaisler, a leading provider of embedded compute for harsh environments, asked us to help verify that its new NOEL-V fault-tolerant RISC-V core was suitable for the final frontier, we knew we had to step back and challenge our assumptions about what “comprehensive” verification really means.

Why Space Changes the Verification Equation

Space is tough on chips. Huge temperature swings, vibration and shock during launch, and a constant background of ionizing radiation mean verification is no longer just about proving that a design implements a specification; it is about demonstrating that the system can withstand a hostile universe that’s constantly trying to break it.

Even for basic chips destined for simple terrestrial applications, verification is often the longest part of development; in my experience it can consume up to seventy per cent of the overall effort. For something like NOEL‑V, which has to be both fault‑tolerant and radiation‑hardened, there are whole extra processes that most designs simply do not require. That makes the verification program even longer and more rigorous.

Nor is it a linear process. Verification is not a single gate you pass through on the way to tape‑out. Even after a version of the processor is produced, the verification work continues towards the next revision, and the next. Field experience, lab data and new requirements all feed back into the verification environment and the test suites. In that sense, NOEL‑V is not just a single chip; it is an evolving platform, and verification has to evolve with it.

From Blocks to System Level Integrity

Traditional verification tends to think in terms of units: block‑level testing, core‑level testing, SoC‑level testing. All of these remain important, but for applications like space, we find it more useful to talk about system‑level integrity.

At Breker we provide a library of SystemVIP components that implement scenario‑based verification environments. For RISC‑V, these include test suites and models for both processor cores and full SoCs, along with dedicated environments for things like coherency, security and power management. The goal is not just to prove that an individual block does what it is supposed to do in isolation. The goal is to demonstrate that the entire system behaves predictably when it is subjected to varied, highly stressed workloads that exercise many features at once.

For NOEL‑V, this meant considering the interactions between the fault‑tolerant RISC‑V core, its caches, Gaisler’s custom error-correcting code (ECC) logic, the wider memory hierarchy and the surrounding system fabric. Space‑grade processors are designed with additional detection, correction and isolation mechanisms. System‑level integrity is about verifying that all of those mechanisms continue to work as intended when the system is pushed far beyond the comfortable corner of a simple unit test.

Synthesizing Strange Corner Cases

Reaching that level of confidence requires more than a long list of directed tests. You need a principled way to explore the dark corners of the state space, particularly the strange corner cases where multiple sub‑systems interact in ways that might be unfathomable to human test writers.

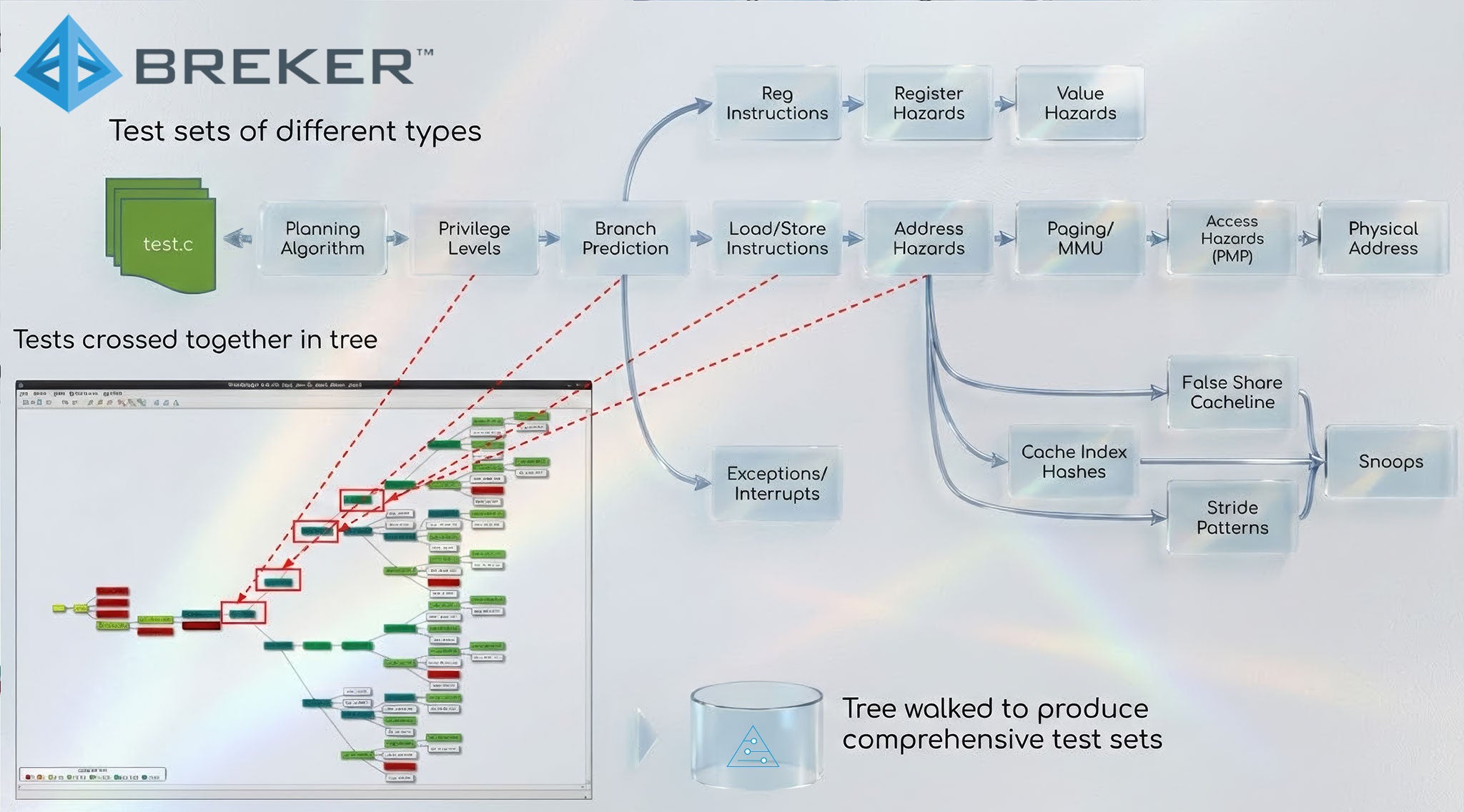

We tackle this by synthesizing tests from abstract models. You can think of these models as graphs or flow charts with decision points and constraints. Our tools flatten these graphs into very large trees of possible test sequences. We then combine trees from different concerns, for example memory ordering, complex addressing patterns, coherency behaviour, security features or privilege changes, to create multi‑dimensional cross‑products of behaviour.

The result is a set of test suites that generate the strangest, least obvious scenarios you can imagine. The crossing of behaviours is multi‑dimensional, so you end up with a very broad coverage spectrum, with all kinds of corner cases being exercised that you would never originally predict. For something like the NOEL‑V processor, which absolutely has to push towards complete coverage, this kind of corner‑case ‘torture testing’ is particularly important.

Another way to say this is that we do not just test to the specification; we deliberately test around it. Positive testing is about checking that the design behaves exactly as the specification says it should. In negative testing, we go looking for trouble around the spec: stressing the design to find the gaps in the implementation or the integration where things could break when pushed in unexpected directions. This is particularly relevant for security testing.

The Customization Conundrum

The RISC‑V ISA adds another interesting layer to this story. One of the most powerful aspects of RISC‑V is its configurability and customization, and I make that distinction intently. NOEL‑V, for example, offers a range of configuration options and can be integrated into application‑specific SoCs and FPGAs. More broadly, we see many RISC‑V‑based designs that add custom instructions, tightly integrated accelerators or security features tuned to a particular workload.

From a verification perspective, configuration and customization are both a blessing and a curse. They let designers build exactly what they need, but they also create a very high probability that changing one part of the design will break something else. The naive approach is to build a test suite for the general processor, then bolt a few extra tests on the end for the customized logic and hope it all works. In practice, it almost certainly will not.

Our approach is different. We let users describe the behaviour of their customized features in the same abstract, scenario‑based way. These models are then plugged into the existing library of RISC‑V tests, and our tools automatically cross them with all the others. That means we are not just testing the custom extension in isolation; we are exploring how it behaves when it interacts with privilege changes, exception handling, memory behaviour, security mechanisms and everything else that matters.

This approach aligns closely with the trend towards workload‑based customizable silicon. With RISC‑V, you can build processors that tightly integrate the ISA, domain‑specific instructions and accelerator logic on a single die. Our job is to make sure the verification approach scales with that flexibility.

Verifying Fault Tolerance, Not Just Functionality

And then we come to the evidence. Space‑grade verification has another dimension beyond functional correctness: it must prove that your fault‑tolerance mechanisms actually work. While there isn’t a single, universally adopted functional safety standard for space, standards such as DO‑254 for avionics and ISO 26262 for automotive capture this in two broad requirements.

The first is systematic testing. You must define requirements, derive verification plans from those requirements, and demonstrate coverage. This is where scenario‑based testing and cross‑product generation fit naturally. By building graph‑based models of requirements and use cases, you can trace your way from the requirement to the test environment and into coverage metrics.

The second is random or fault-based testing. You must show that if nodes in the design are disturbed by interference, the system either continues to operate correctly or fails in a controlled, detectable way. A fault simulator can, for example, mimic the effect of a solar flare by walking through the chip’s registers, memories and internal nodes, flipping bits one by one. Mutation analysis then checks whether each injected fault actually changes observable behaviour, and whether your testbench is sensitive enough to catch it.

In a design like NOEL‑V, these techniques are combined with dedicated tests for ECCs and memory protection. Traditional ECC schemes such as BCH codes might correct single‑bit errors and detect dual‑bit errors. Gaisler has gone further, with more specialized algorithms that can detect a wider range of error patterns in caches and memories, along with hardware scrubbing to prevent errors from accumulating over time.

Verification has to prove not just that those mechanisms work in isolation, but that they behave correctly when exercised as part of realistic, stressed system‑level scenarios.

Will “Space‑Grade” Verification Become Table Stakes?

My hope is that this level of verification becomes table stakes for anything that is up in the sky or carrying people. That includes other spacecraft and satellites, avionics platforms and advanced air mobility systems. Automotive chips, particularly those for driver assistance and autonomous driving, are moving quickly in the same direction. Industrial control, rail and critical infrastructure markets are not far behind. All of these domains require evidence that the electronics will behave predictably under rare but consequential events.

I do not expect full, exhaustive fault simulation to be applied to every single chip in every market. That would be prohibitively expensive in simulation time and compute. But I do believe that broad, scenario‑based, system‑level coverage, rich corner‑case exploration and explicit negative testing should become non‑negotiable for any system where failure is unacceptable.

As systems become more complex, and as they take on more autonomy, it simply becomes harder to predict what they will encounter in the field. Verification will need to evolve to anticipate this unpredictability.

RISC‑V’s role in this evolution is subtle but important. The same base architecture can be used across many markets, from consumer devices to deep‑space missions. That means verification environments and test suites must be robust enough to support a wide range of configurations and end uses. Techniques that we refine on space‑grade designs such as NOEL‑V will increasingly define how the industry approaches safety‑critical verification more generally.

Designing For an Unforgiving Universe

Gaisler already has processors flying across the solar system, from Mercury to Neptune. Sitting at the heart of its upcoming GR765 radiation-hardened space microprocessor, NOEL-V represents the cutting edge of its capabilities. When it comes to verifying a processor as mission-critical as this, “good enough” is never enough; the universe will exploit any weakness you leave behind.

Gaisler already has processors flying across the solar system, from Mercury to Neptune. Sitting at the heart of its upcoming GR765 radiation-hardened space microprocessor, NOEL-V represents the cutting edge of its capabilities. When it comes to verifying a processor as mission-critical as this, “good enough” is never enough; the universe will exploit any weakness you leave behind.

That is why we focus on system‑level integrity rather than just block‑level correctness; why we synthesize multi‑dimensional corner‑case tests rather than relying only on human intuition; and why we treat fault‑tolerance, not just functionality, as a first‑class verification goal. Space may be the most visible example of a zero‑margin environment, but it’s far from the only one. The techniques that make a RISC‑V core like NOEL‑V trustworthy in orbit will increasingly shape what “good verification” looks like for the rest of the industry as well.

For verification engineers, that is both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge is to build environments and methodologies that can keep up with a world (and a universe) that does not forgive mistakes. The opportunity is to help create systems that are not only more powerful but fundamentally trustworthy, whether they’re on the ground, in the air, or far beyond our atmosphere.

RISC-V in Space

RISC-V processors deliver configurable, fault-tolerant compute for satellites, robotics and advanced payload instruments across future missions. Discover the architecture that is rapidly becoming the common language of spaceflight.